Heat Training for Triathletes: The Science-Backed Performance Boost You Might Be Overlooking

Imagine training hard all winter, swimming countless laps, biking for miles, and running intervals. You feel ready. But on race day, unexpected heat hits, and by the third mile of the run, you’re struggling while others seem fine. Has this happened to you?

Here’s what most triathletes don’t realize: heat tolerance isn’t just about toughness or hydration strategy. It’s a trainable adaptation that can dramatically improve your performance. Even more surprising? The benefits extend well beyond hot race days.

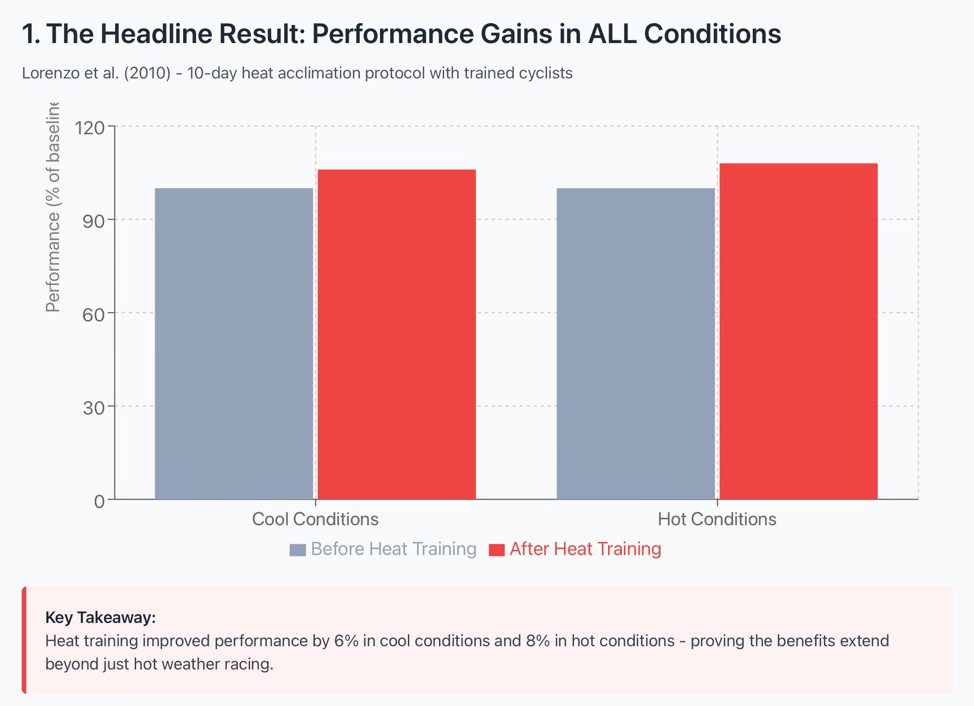

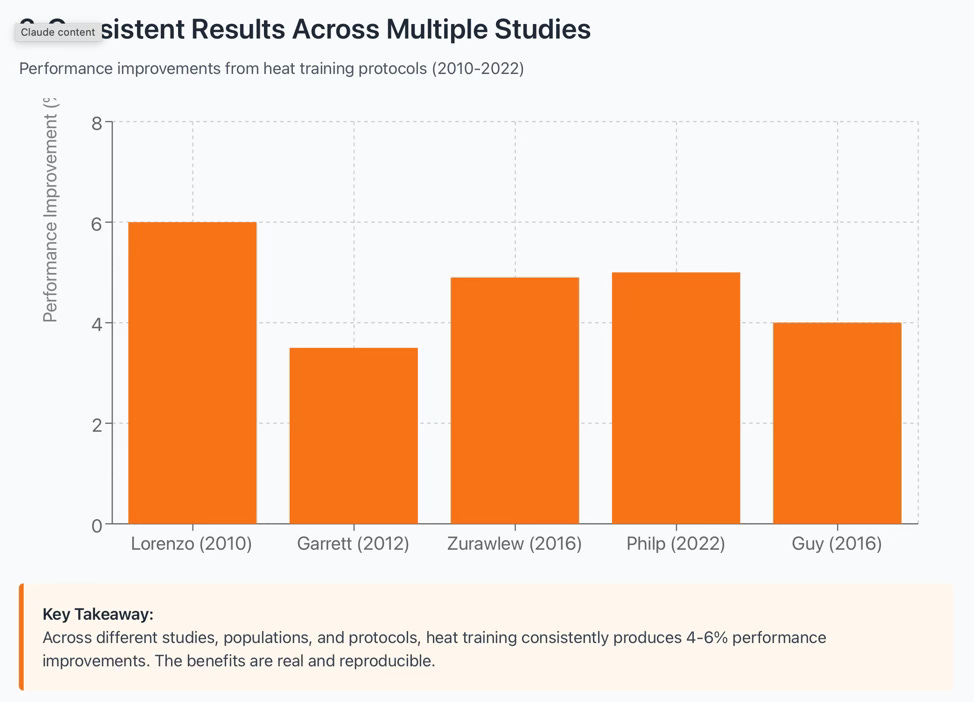

Studies from 2010 to 2025 show that focused heat training can boost endurance performance by 4-8% in as little as 10 days to 3 weeks. That kind of progress could move you from the middle of the pack to the podium. Surprisingly, these gains also appear when racing in cooler weather.

Why Heat Training Works (And It’s Not What You Think)

When you train in heat, your body undergoes significant changes beyond just learning to sweat better. These changes help your heart, blood, and how your cells use energy, making you perform better in any weather.

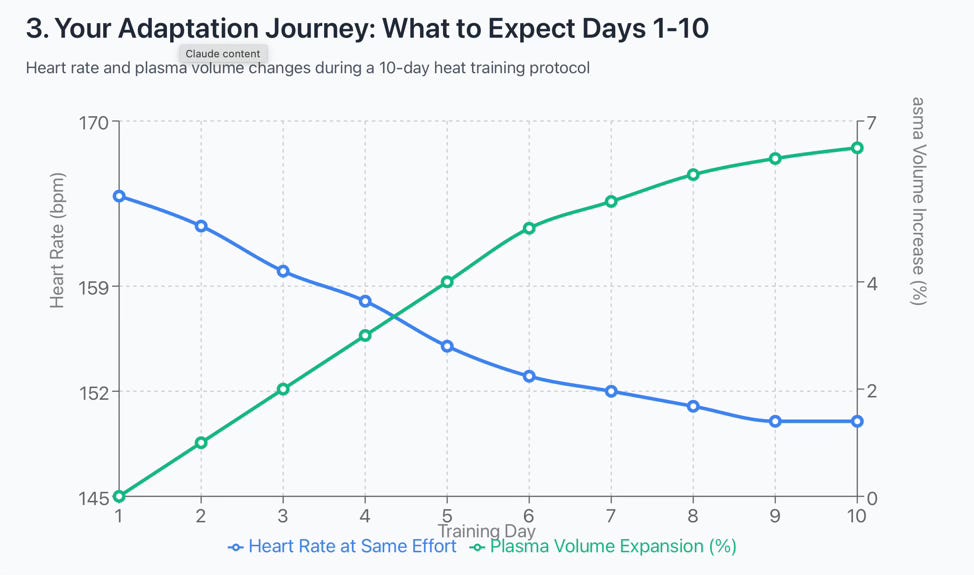

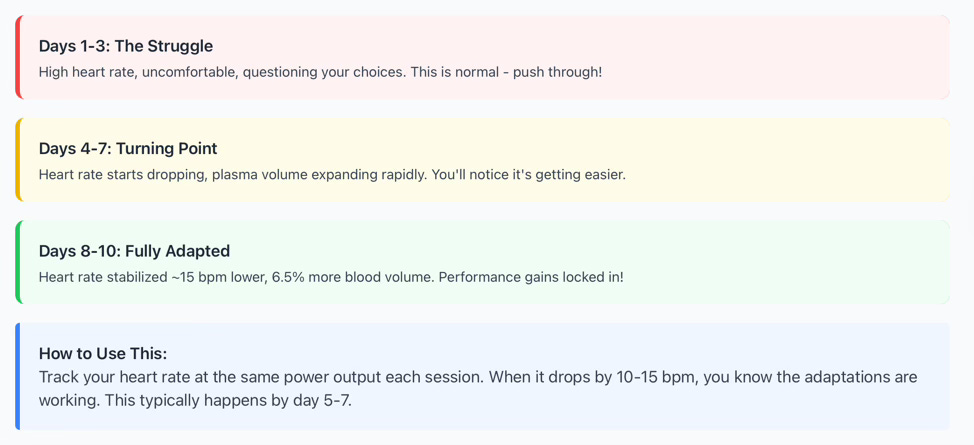

One of the biggest changes is an increase in the liquid part of your blood, called plasma. After just 5-10 days of heat training, plasma can rise by 3-7%. This isn’t just about drinking more water. More plasma means your heart can deliver more oxygen to your muscles with every beat, making your body’s delivery system more efficient.

Your heart and blood vessels also become more efficient. Research shows that after adapting to heat, athletes have lower heart rates for the same effort, their hearts pump more blood, and their bodies manage temperature better, even in cooler conditions. Your body learns to work more efficiently.

Heat training also affects hemoglobin, the protein in your blood that carries oxygen. A major 2025 review found that 3-5 weeks of heat training increased hemoglobin levels. While the performance gains might not be as large as earlier studies claimed, these body changes are real and measurable.

What The Research Actually Shows

Now, let’s review some key studies that have shaped what we know about heat training for endurance athletes.

The Lorenzo Study (2010) changed the game. Cyclists completed 10 heat sessions over two weeks while continuing their usual training. The results showed a 7% improvement in time trial performance in hot weather and a 6% improvement in cool weather. This study showed that heat training isn’t just for coping with hot races—it can make athletes faster overall.

Garrett’s Work With Rowers (2012) showed similar results with a slightly longer protocol. Nineteen rowers completed 5 days of heat training over 9 days. Their 2000-meter time trial performance improved by 1.3% in temperate conditions, with power output increasing significantly. For context, in elite rowing, a 1% improvement can mean the difference between making the podium or finishing sixth.

The Hot Bath Protocol (2016) gave amateur athletes hope. Researchers at Bangor University demonstrated that something as simple as a 40-minute hot bath after training could trigger heat adaptation. Runners who followed a 6-day protocol of treadmill running followed by hot water immersion (40°C) improved their 5km time-trial performance by 4.9% in the heat. Their core temperature dropped, heart rate decreased, and perceived exertion plummeted. Best of all? This method requires nothing more than a bathtub.

Real-World Application (2022) was based on work with national-level rowers. Researchers had elite athletes replace some cross-training with 10 heat sessions at 34°C. The protocol was designed to integrate seamlessly into existing training—no disruption to key workouts. Results showed significant improvements in 4-minute power output tests and a substantial increase in plasma volume. The key insight? Heat training doesn’t require sacrificing your regular training; it can enhance it.

The Safety Study (2016) addressed a critical concern. Athletes worry that adding heat stress might compromise immune function or increase injury risk. Guy and colleagues followed recreationally active cyclists through an 18-day protocol with 7 heat sessions. Not only did performance improve significantly, but researchers found no adverse effects on immune markers or endotoxin levels. Heat training, when done correctly, is safe.

The latest evidence is from Lundby’s 2025 review in the Journal of Physiology. This analysis shows that while heat training reliably leads to changes in the body, especially in hemoglobin mass, the performance gains are usually modest. The review suggests heat training is most effective when your basic training is already solid and may be better used instead of altitude training, not on top of an already busy schedule.

Three Practical Protocols You Can Start Today

One great thing about today’s heat training research is that you don’t need special equipment or a lab. Here are three proven methods that amateur athletes can use:

The Hot Bath Method is the easiest to try. After a moderate workout (60-75% of your maximum heart rate), soak in a 40°C bath for 40 minutes. Your core temperature will keep rising even after you finish exercising. Repeat this 5-6 times over 7-10 days. The Zurawlew study found that this simple routine leads to real changes. Use a thermometer to check the water, stay hydrated, and pay attention to how you feel.

Indoor Training Sessions work if you have a home gym where you can control the temperature. Turn up the heat to 34-38°C and set the humidity to 60-70%. Do 60-90 minute workouts at a steady, moderate effort (about 55-65% of your maximum effort or Zone 2 heart rate). The main goal is to keep your body temperature higher, not to push yourself to the limit. Ten sessions over 2-3 weeks can lead to significant changes. Several studies, including the Lorenzo and Garrett plans, used this method with excellent results.

Sauna Protocols offer flexibility. After your workout, spend 20-30 minutes in a sauna at 80-90°C to get similar benefits. Some athletes prefer this because they can sit in the heat instead of exercising in tough conditions. While research on sauna-only methods is still developing, the body’s response is similar to the hot bath approach.

Who Should Consider Heat Training?

Heat training isn’t right for everyone, and timing is important. The 2025 Lundby review points out that heat training shouldn’t replace the basics. If you’re still building endurance, working on training consistency, or focusing on recovery, make those your main priorities first.

Heat training is best for athletes getting ready for a hot-weather race, who already train consistently, want small extra gains after improving other areas, or need an alternative to altitude training. If you’re racing an August Ironman or a summer marathon, the 10-14 days before your event are ideal for a heat adaptation block.

People respond to heat training differently. Some athletes handle heat stress well and see big improvements, while others find it more difficult. Research shows that what works great for one person might not help another as much.

If you’re sick, injured, already under a lot of training stress, or new to endurance sports, it’s best to wait before trying heat training. Make sure you’re ready to handle the extra stress first.

Getting Started Safely

If you want to try heat training, begin slowly. Make your first session shorter and easier than your target. Notice how you feel, and gradually increase the length and temperature of your sessions. Using a CORE sensor to track your body temperature can help you see how you’re handling the heat and keep your training safe.

Staying hydrated is even more important during heat training. Drink extra water before, during, and after your workouts. Consider adding electrolytes, especially sodium, to your drinks. Weigh yourself before and after each session to see how much water you lost. For every kilogram you lose, you’re about one liter low on fluids.

Look out for warning signs such as dizziness, nausea, confusion, cessation of sweating, or feeling very uncomfortable. These are signs you’ve pushed too far. Stop immediately and take extra time to cool down. Heat training should be tough but always safe, not dangerous.

Rest is especially important during heat training. The extra stress on your body is real, even if your workouts aren’t very intense. Be sure to get enough sleep, eat well, and include easier training days between heat sessions. It’s a good idea to scale back your other workouts to manage the added stress.

The Bottom Line

Heat training is one of the most well-studied ways to boost performance in endurance sports, with research covering 15 years and many different methods. The science is clear: planned heat exposure leads to changes that improve your heart’s efficiency, oxygen delivery, and temperature control in all race conditions, not just in the heat.

For amateur triathletes, practical options like hot baths, heated indoor workouts, or sauna sessions are easy to access and don’t need expensive gear or big changes to your training. While the improvements may be modest, as recent research shows, they can still offer real benefits when used wisely.

The main point is to see heat training as a focused tool, not a miracle solution. It works best when it’s part of a well-planned training schedule, timed right in your season, and adjusted for your personal response. If you’re racing in summer heat or want to improve your heart and blood adaptations, heat training is worth considering.

Start cautiously, pay attention to how your body responds, and remember that the goal isn’t to push through extreme heat sessions. The aim is to create changes that help you perform better when it counts. Your next big improvement could come from simply raising the temperature.

Thanks for sharing and super thoughtful to include methods to try at home 👏🙏